We are so addicted to patterns that we let them sneak into almost everything we do. Moreover, these patterns are the key to predicting many aspects of our behaviour, even the darkest parts of our nature.

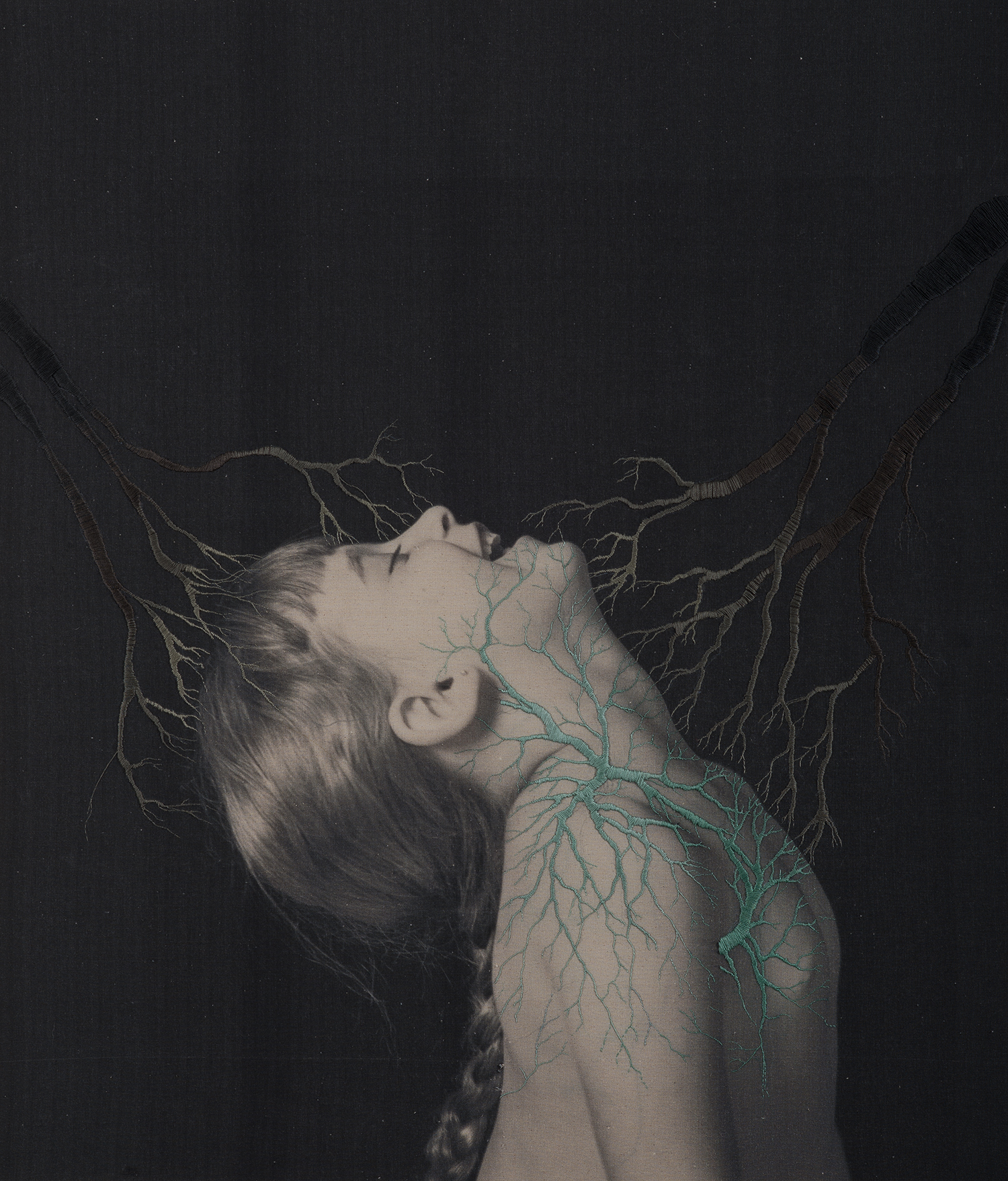

During the last years, Juana Gómez’s work has intertwined science with ancestral knowledge. In other words: entangle our understanding of reality, which stems from concrete evidence, with what we, inexplicably share, with our ancestors, or other life forms. Her work opens paths towards multiple timelines and knowledge in a tight relationship with the maternal legacy of embroidery, reminding us of our primeval bond to our mother by a cord. This cord must be cut so that we can enter into this world and breathe for ourselves. The artist’s photographs are printed on raw fabric – made by hundreds of threads that intertwine to form a whole – and it literally becomes our second skin. The fabric, which relates to our body’s largest organ, guides the embroidery, which unites our scientific, spiritual and mythological body.

A distaff is an English word that describes the matrilineal branch of a family. Its association with the mother originates from communities that symbolized the domestic life with a tool that bears the same name, used for manually spinning fleece. This crossing of meanings is embodied in the figure of the Germanic goddess Figg, wife of Odin, goddess of marriage, childbirth, motherhood, home care, weaving, spinning, and the sky, from where she weaves the clouds and winds the threads of destiny. Juana Gómez, like Figg, is bound to a course – guided by her oracular vision – that guides and gives continuity to the blood ties of her genealogy. She brings with it multiple symbolic and physical relationships embodied in the photographic series that make up this exhibition, portraying her and her daughter Julieta, along with the hands of her family’s women, including her mother and grandmother.

One of the central pieces in this exhibition, The Pattern of Origin, engages the faces of mother and daughter in perfect symmetry, generating the illusion of a mirror in which both could be the same person at different ages. The daughter’s body has a representation of the lymphatic system embroidered over it. This system’s function is to maintain our immune system’s balance; it symbolizes protection, our defense shield of everything unfamiliar. This symbolism is reinforced in the oeuvre by the mother’s attitude of covering her vision, as if to protect the daughter from an immutable destiny and immediate memories, seeking to microscopically transform her genetic map with small gestures.

A few years ago, the artist tattooed a crow on her right hand. This bird represents ancestral memories, and although this bird is perceived as an animal linked to death, it also possesses the gift of vision. According to some myths, it flew out of the cosmos’ dark womb to bring sunlight (or knowledge) to humankind. This solar animal embodies the bridge between light and darkness, between ancient wisdom and the transforming power of the novel. On the artist’s body, it is an indelible amulet, and on the photographic image, its presence is reinforced by the black stitches of the embroidery. In the same oeuvre, the artist weaves a silver threaded lung over her breast, establishing a delicate connection with the air. The connection is also with the subtle and the oneiric; with what is transferred in the dreams; with the intuition that guides the hand, alluding to the tradition of some ancient ethnicity in which the weavers had to be designated by their ancestors through a dream.

The black background of some of the works transports us to the place from where our patterns come. In addition, it takes us to the darkness of the photographic laboratory, where the chemical processes occur, and images can be modified. For the artist, the image’s transformation is linked to her own transformation, which takes place on multiple sensory levels. Hence, many of the chosen patterns: organs, cells, microorganisms, etc. evoke the amplification of our perceptive capacities to an almost mediumistic level, where diverse temporalities unite, projecting an always-present origin. Our ancestors, like our successors, are the physical evidence that we are but a part of the chain of existence, situated in a particular place and time. Man’s history and evolution cannot be thought of as something occurring independently of the self, rather, history and evolution have helped us inherit humankind’s universal mind, to think and act in synchrony with a structure of consciousness much larger than our limited conceptions.

Often, science reminds us of our origins, questioning the limits of our capacities. Today, it invites us to ponder on the interconnection between us and all the species that live or have inhabited the universe. This is a necessary condition for the transformation and conquest of new physical and mental territories. In two of the exhibited works, mother and daughter appear in a position that gives prominence to their backbones. Julieta turns her back to the camera revealing only a braid that binds her hair and fuses with her backbones; Juana looks sideways over her shoulder exposing the area of the nape of her neck and her shoulder blades. The two images are embroidered with red and blue threads, representing the circulatory system. They reveal the vital fluid that passes just a few millimeters below our skin. Most particularly, it emphasizes human evolution, whereby our spine represents our ability to stand, and in the relationship between the past and the future.

The maternal bond is undoubtedly one of the strongest and most persistent; during the 80s science has discovered a molecule that is only inherited through mother to daughter, called the mitochondrial genome. Since this genetic material does not recombine, it passes from generation to generation with few modifications, allowing for the consideration of a possible original ancestor appropriately called mitochondrial Eve. Theoretically, she could be our original mother, our most recent common ancestor, dating back to some 190,000 years. This prolonged genetic inheritance may be perceived as a silent transfer of motherhood, of all that comes from the womb, of the deep secret of the matriarchal vision and its relation to the cycles of nature. The details of the hands represent the inheritance of the embroidered and craftsmanship. However, they bear more than just one meaning. It is possible that at the origin of history, women possessed an ancestral secret of communion with the cosmos, where they were responsible for elaborating interpretations of the world as complex as those we know today, to inhabit it and to connect with it. Being together and sharing the depth of our existence has led to the creation of domestic chores (the distaff) assigned to women for centuries, and currently diluted by modernity. However, in Juana Gomez’s work, these recover strength in need to honor biology itself.

Juana Gómez’s work is a tribute to our kinship. Above all, it is an invitation to observe the patterns that determine our behaviour. Through the threads and embroidery, it invites us to question what must be cut or woven, to advance as a species. To consider how humanity and its kin can have a future opportunity in harmony and respect with our ancestors.